Time to read: 9 min

My favorite type of product is one that I hardly notice—something that’s in my life every day, improving it significantly, yet blends seamlessly into my routine. For example, a wristwatch fits gently but snugly around your wrist, keeps time with a tiny precision mechanism, is easy to glance at when you need it, and fades from perception when you don’t. It’s a timepiece, a fashion statement, and perhaps your internet, mail, phone, and Rolodex, if it’s a smartwatch—all in a convenient package of metal and textile.

But the wristwatch didn’t just appear in our lives as a singular invention—it’s the result of decades of refinement of design and engineering, and many of these iterations were brought about via a human focus, rather than a technical one. Instead of asking what’s wrong with an existing version of something, good designers ask what the users need but don’t yet have. They ask this over and over, focusing on user needs and stripping away the excess, until the product provides such an intuitive experience that it becomes ubiquitous within its space.

Over time, this methodology has come to be known as Human Centered Design (HCD). In this article, we’ll be taking a look at the various components involved in HCD, as well as how you can leverage the process to develop marketable products that provide a lasting impact.

A Brief History of HCD

HCD has been used implicitly in design and product development for as long as there have been things to design and products to develop. The term “user-centered design,” however, was not coined until 1986, in a research lab at the University of California, San Diego by psychologist, engineer, and mathematician Donald Norman.

Norman’s book The Design of Everyday Things outlines the psychology behind good and bad design and argues that user needs should take center stage in the process. Things like aesthetics are second to, or even a result of, good needfinding and iteration.

Since then, the methodology has been adopted, expanded, and further developed by many players in the design industry, and is now also commonly known as HCD. In the Bay Area, Design Thinking is a method popularized by design firm IDEO and its educational cousin, the d.school at Stanford University. Design Thinking is essentially a form of branded HCD, focused on empathy-informed problem solving.

The Cyclical Nature of HCD

Of equal importance to empathy in this framework is the idea that a well-developed product is one that has been taken through several cycles of divergent and convergent ideation. With HCD, this process is split into three major phases:

-

Inspiration – divergent exploration of the product space

-

Ideation – repeated experimentation with various product components

-

Implementation – synthesis of a refined product with its most critical requirements

Throughout these phases, elements of the design space are explored, tested, and whittled down until only the essentials remain. If one hits a roadblock during any phase, however, it is perfectly acceptable—and sometimes even desirable—to diverge again.

As we examine each stage of the HCD process, we’ll look at applications of the theory. I’ll also discuss a few aspects of my graduate “thesis,” a year-long product development course, to illustrate a singular application across different areas of the methodology.

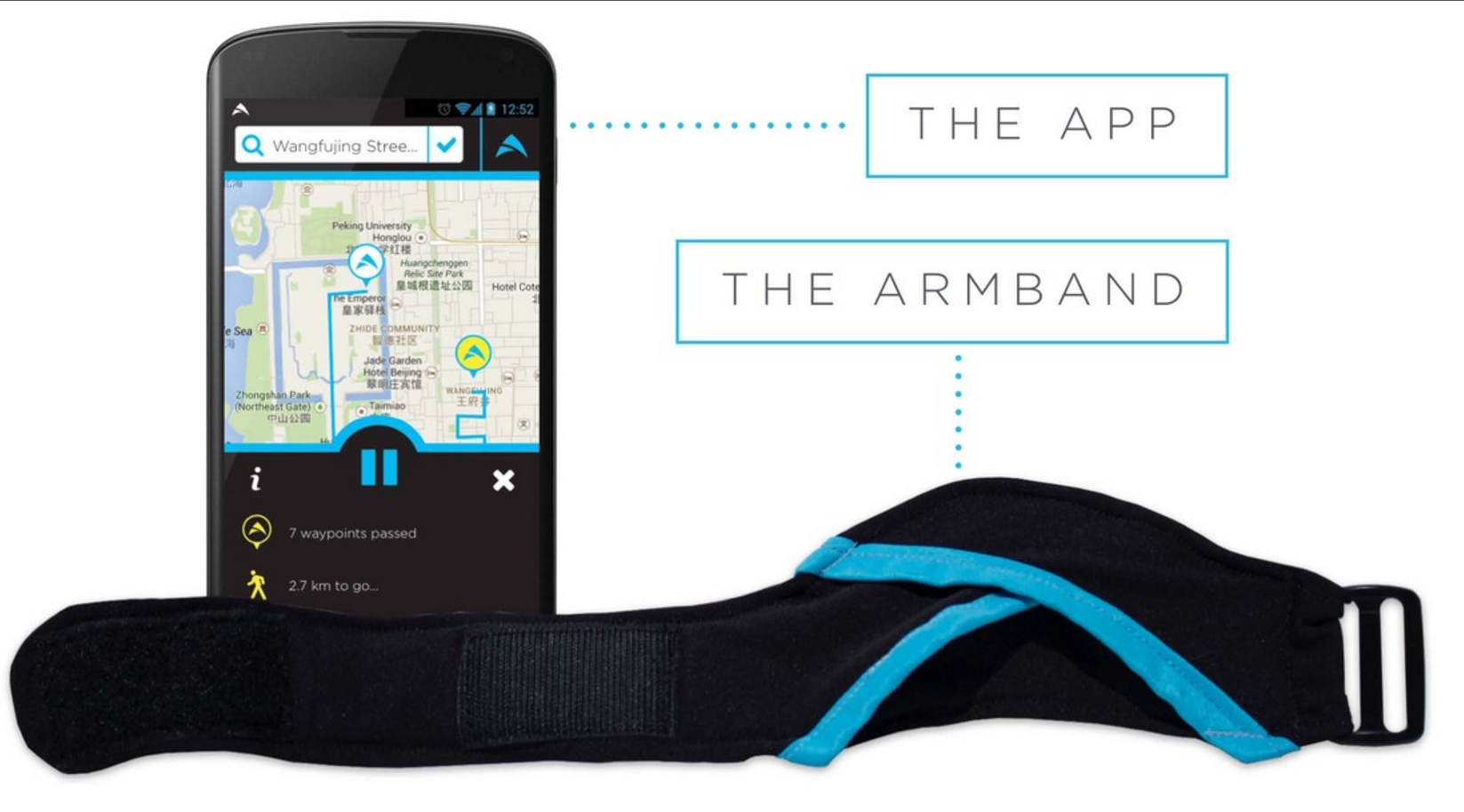

In this course, my team was tasked with creating a “wearable artifact that augments and extends the capabilities of [humans].” The result was a haptic (touch-based) navigation wearable for pedestrians, called Romu.

Inspiration

The first general phase of HCD methodology is design inspiration, gained through exploration. Exploration, that is, of the general design space or industry segment within which we’re working. After all, if we are uninformed about for whom we’re designing, and what else already exists in the space, how can we develop a truly useful product?

Needfinding

The easiest way to jump into the exploration phase is through needfinding. Needfinding is the process of watching and asking people about their habits and values, in order to identify user needs and areas for improvement. By repeating this process many times with a diverse sample group, we can develop a clear snapshot of our design space and the problems/opportunities within it.

If there are existing notions or ideas about the space, it’s also a good idea to present super rough prototypes to users during this exercise. It’s amazing how useful a cardboard and duct tape mock-up can be in jump-starting conversation, testing existing hypotheses, and failing faster!

The Node chair (by IDEO and Steelcase) is a product with design elements clearly informed by the needs of today’s dynamic classroom environments. From its ergonomic shape and storage features that offer comfort and convenience, to its swivel and roller mechanisms that allow ultimate flexibility between personal and group activities, the Node is the answer to many woes that were previously commonplace in the academic world.

Developing a Persona

After a bit of needfinding, we begin to see the details of our user(s) emerge—who they are, what they like and dislike, what their challenges are, etc. This is called the user persona, and it’s for whom we’re designing.

Some people like to define the fine details of their persona to get a very clear design direction. I’m of the opinion this is unnecessary and is in fact a transition to convergent thinking too early on. As long as a general user profile is outlined, some good ideas for the next stage should start flowing.

The persona that led to Romu was a young urban professional (most of our needfinding was in cities) who travels often to new areas for work or for fun and is eager and willing to adopt new technology.

Benchmarking

Another step of the exploration stage is benchmarking. With a general user and design space defined, it’s important to look into other products and services already in existence, to get an idea of what is out there and how it can be improved.

Let’s look at how proper benchmarking led to Ox, a flat-pack all-terrain vehicle that can be shipped worldwide and assembled by three people in about twelve hours (with huge humanitarian and logistics implications for remote areas, like those in Africa). It was designed by a former Formula One designer with a deep knowledge of existing materials and technologies and decades of experience implementing design principles like robust, lightweight construction. Simultaneously, the Ox draws inspiration from furniture designers like Ikea, as exemplified by its easy, out-of-the-box assembly.

Benchmarking does not necessarily have to be done after needfinding and persona development, but this helps narrow the focus a bit. You can also look into products that don’t fit your persona if they still relate to your design space!

Ideation

Phase two of HCD methodology is ideation—the creative process of generating, developing, and communicating new ideas related to your design space. The goal here is to test hypotheses about the space, get feedback, and refine your design requirements.

As with prototypes used during needfinding, failure here should not be frowned upon. If an idea does not work or is poorly received, take that as progress and knowledge of a path not to go down! Similarly, a prototype may generate more questions than it answers, and this is ok, too.

Prototyping Sprints

Ideation is usually best done through a series of prototyping sprints. These quick-turn proof-of-concepts allow for rapid iteration of an idea—or several ideas in parallel—to synthesize information and refine a design component quickly and efficiently.

Take Under Armor’s Magzip, for example, which allows for one-handed zipper engagement and operation, through the use of a clever magnetic latch mechanism. The creator of this device originally thought of the idea while brainstorming ways to help his sick uncle.

What started off as magnets on a zipper eventually became a patented system with a refined hook-and-catch and enclosed magnets. But it wasn’t instant success—this development occurred over 25 iterative prototypes of various design configurations and tweaks.

Forcing a Pivot (Dark Horse theory)

One HCD technique used in my grad work, which I haven’t heard so explicitly stated elsewhere, is the Dark Horse theory. This theory encourages the execution of a pivot, or change in direction, at some point during the Ideation phase. In other words, build and test a prototype to answer a completely different (and usually provocative) question than before—a Dark Horse.

Seemingly a long shot, this exploration can uncover new insights and even “unstick” you from a stale path by redirecting your focus elsewhere. You don’t have to stick with the new direction, but it’s not uncommon!

The Romu team, for example, pivoted several times. We briefly looked into connected facemasks for pollution detection, visual/wearable expression of emotion and mood via biometric sensing, and even smart condoms that would alert users of defects and expiration. We eventually returned to haptic navigation (arm-mounted, this time), but our learnings along the way were critical to our final prototype.

Implementation

The third and final phase of HCD methodology is implementation. Congratulations, the end is in sight! Now, it’s time put everything together and make a badass, life-changing product.

Make a Plan

Once you have a list of specifications that addresses the most core user needs, it’s easy to want to speed off and create a final prototype or end product. STOP. Use this excitement to take a breather and plan an attack. The implementation phase should be a strongly convergent one, and when there is no structured approach to the homestretch, there is serious risk of design creep, when ill-defined requirements and extra features can bog down, or even kill, a project.

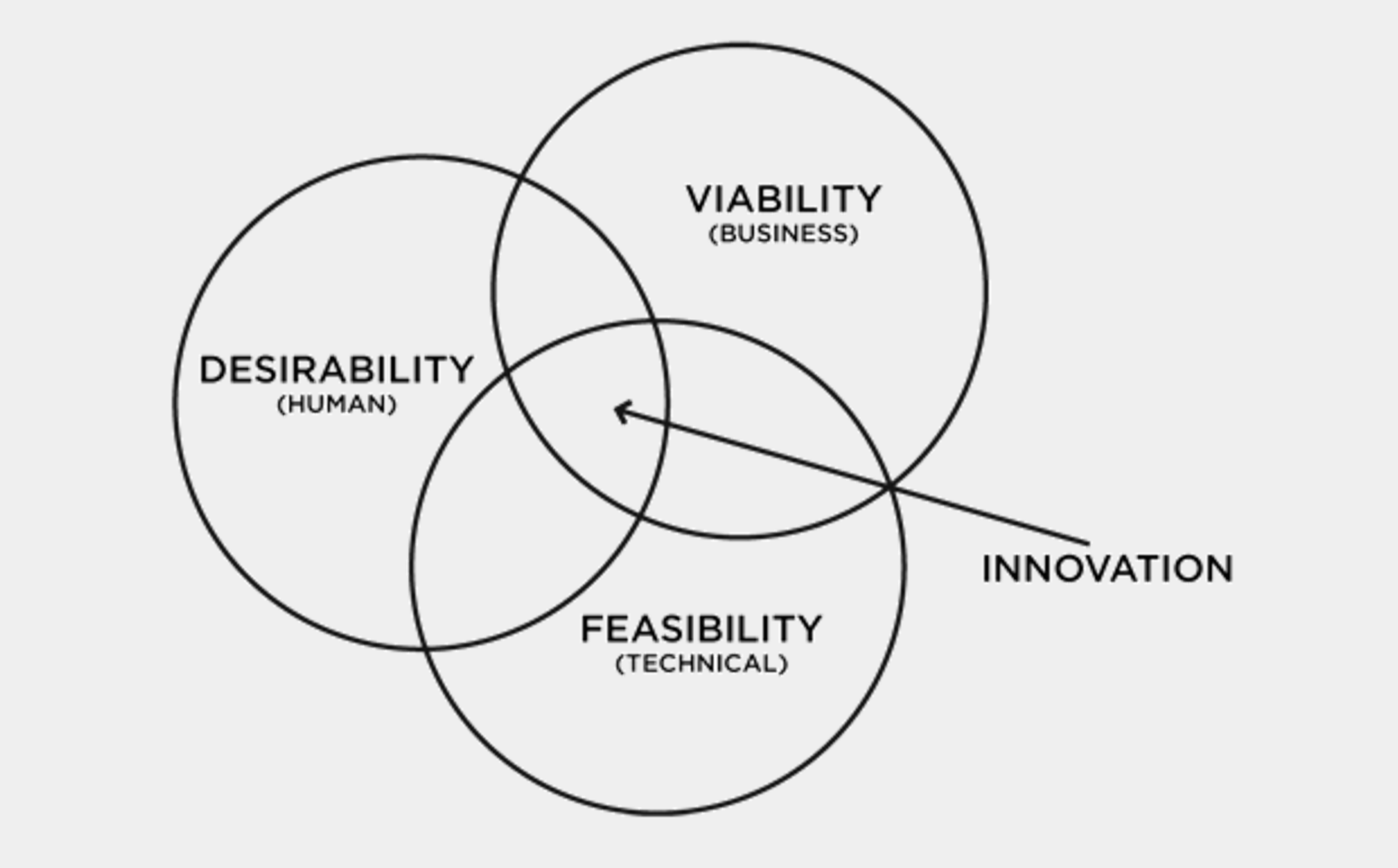

In an ideal scenario, we’d fulfill all the human needs and solve all the pain points observed through research. However, in a business setting, we have limited resources and time, and the best path forward should be sustainable for the business, feasible to implement, and desired by the user.

Using the insights found in the field and through prototyping, we can better engage stakeholders, guide product development, and boil down the list of specs into the most essential set.

It can also be a good idea for different members of the team (assuming you are not solo) to manage separate components of the plan, such as scheduling, manufacturing, and budget. Dividing and conquering holds everyone accountable and allows for a project of considerable complexity to still be completed efficiently.

Finish A Key Component

Set a hard deadline for the first complete subsystem. This is usually the subsystem with the critical functionality for the product, and gives a solid foundation to design and build around.

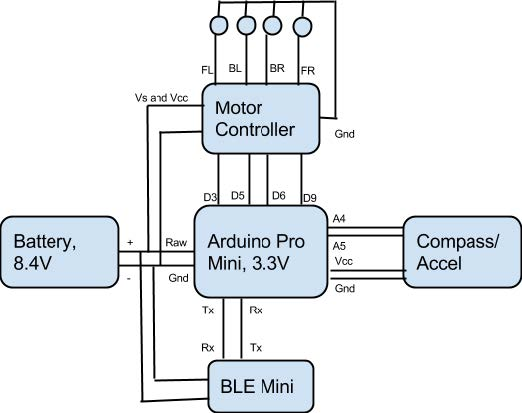

Romu’s first completed subsystem was the vibration motor array and software navigation protocols. If people couldn’t use the haptic cues to navigate a foreign area turn-by-turn, our product was dead in the water. After this feature was complete, we moved on to the other subsystems—armband, electronics enclosure, app, Google Maps and Bluetooth integration, and power supply.

Systems Integration

After all design components are performing on their own, they must also function together. Imagine that! This step is often surprisingly tricky, and there are almost always unforeseen issues, so plan for some frustration. Let’s just say that twelve hours before pitch day, half of our ten Romu armbands were still non-functional.

Reveal!

Once our product is assembled, functioning, and looking pretty, we get to show it off to the world! Whether this is a polished prototype being pitched as a business idea, or a shelf-ready product, if we’ve followed the HCD methodology, hopefully we have something with elegant design and true utility.

Again, remember the emphasis on user needs at this time. Engineers tend to list out all the technological features and functionalities of the product, which tempts the audience to ask, “So what?” Instead, think back to some of the users you encountered during development, and tell the story of the product as if they were the ones using it. This helps the audience relate and invites clearer feedback from stakeholders.

Main Takeaways

If there was one word to sum up the process of Human Centered Design, it would likely be exploration. A deep and thorough dive into a design space is what leads to excellent product design and true innovation. Rather than settling on an idea and direction early on, it’s better to test the various components of it repeatedly. Keep brainstorming, prototyping, and iterating, understanding that failure is not something to be feared, but rather a tool to be utilized for breakthrough, until only the core user needs are realized, empathized with, and solved.