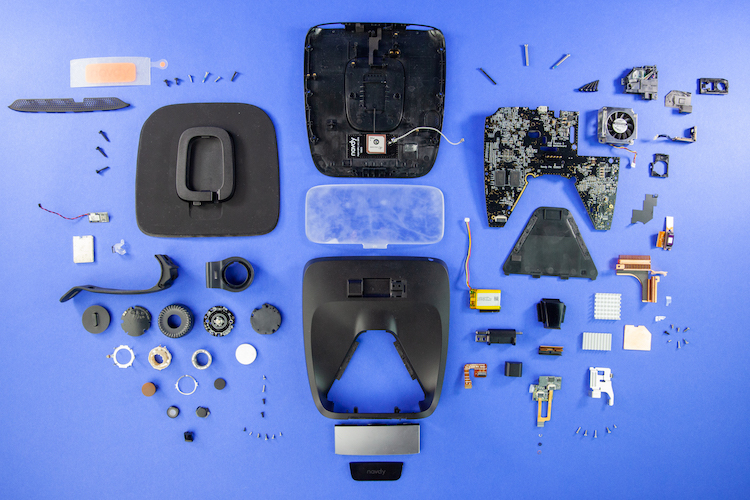

For this teardown, we’re joined by Telind Bench, the Lead Product Design Engineer for Orion Labs. Telind gave us a lot of great design insight into the Navdy Heads Up Display (HUD).

In case you missed it, the Navdy Head Up Display was one of the more interesting new products announced in 2014. It promised augmented reality for any vehicle, adding gesture control, navigation, phone calls, and a host of other features to its Kickstarter backers, for only $299.

More remarkable still, Navdy would provide all of these features from atop your vehicle dashboard—humming along at temperature extremes that can bake cookies or make instant slushies. To do that, it packed a full Android processor; Bluetooth and GPS antennas; and even a tiny projector into a beautiful, seamless-looking housing.

After a year and a half of delays, Navdy officially launched in late 2016, to largely positive reviews. However, it was not fated to last. By the end of 2017, Navdy publicly announced its liquidation and notified users that their devices would soon stop working.

So, what happened? We were curious to see what the Navdy HUD could tell us about the meteoric rise and fall of the company and whether there are any takeaways here that could improve our designs.

Here are the features of interest we’re drilling into for this teardown:

1. Clever design for injection molding – We found some really elegent design for injection molding, with some great lessons.

2. Heat sinking – Tearing down this product was basically a tour of different heat sink technologies. There are 5 different heat sinks on the Navdy, all optimized for different things.

3. Attention to detail – It’s clear that the Navdy team put a lot of thought and heart into creating every part of this system, including small features like the thumbwheel.

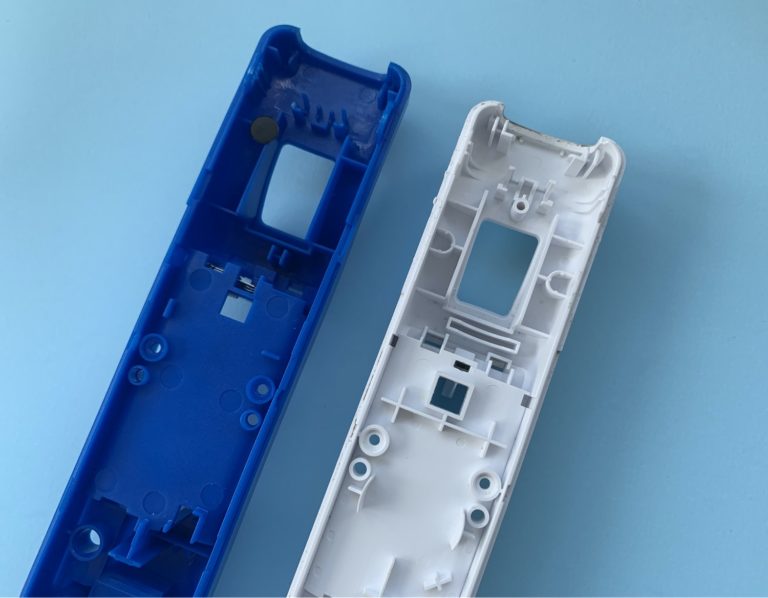

Design for Injection Molding

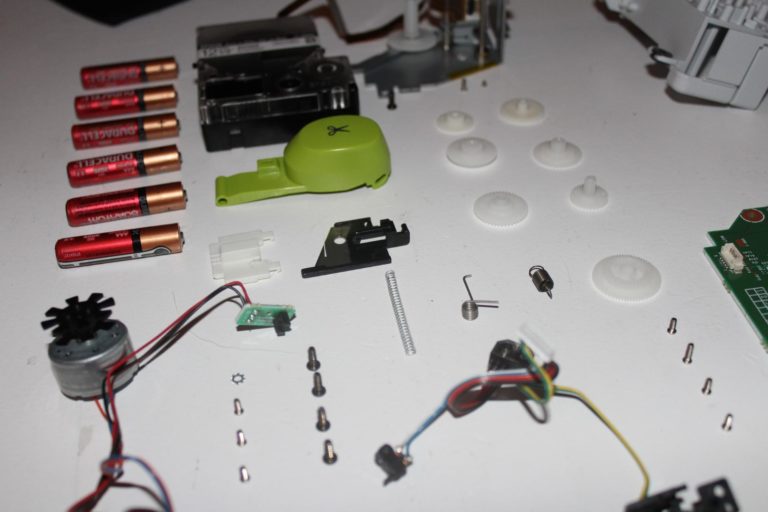

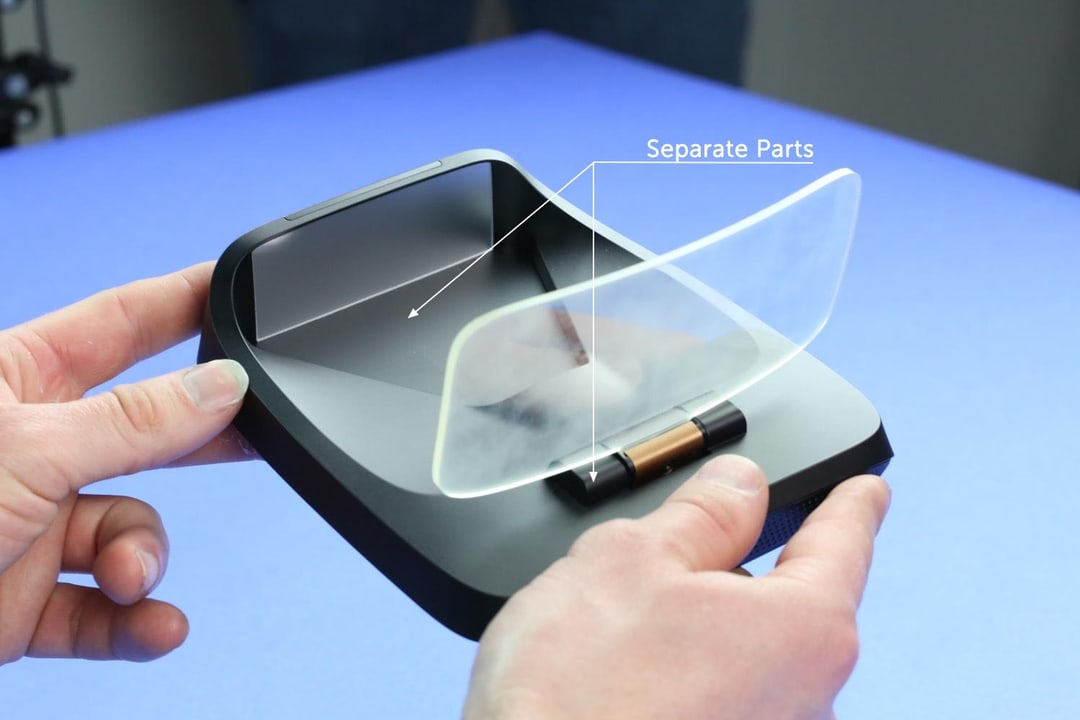

Tearing down the Navdy HUD, we found some really elegant design for injection molding. Over and over again, the Navdy team broke large, complex parts into smaller, easy-to-mold parts.

This strategy increases part count but can be helpful if the parts would otherwise be too complex or the molds too expensive. This can be taken too far (like on the Coolest Cooler), but in this case, it allowed Navdy to have both the exterior surfaces and the interior geometry they wanted.

Navdy engineers cleverly hid all of the parting lines using corners in the industrial design, making the assembly appear seamless from the outside.

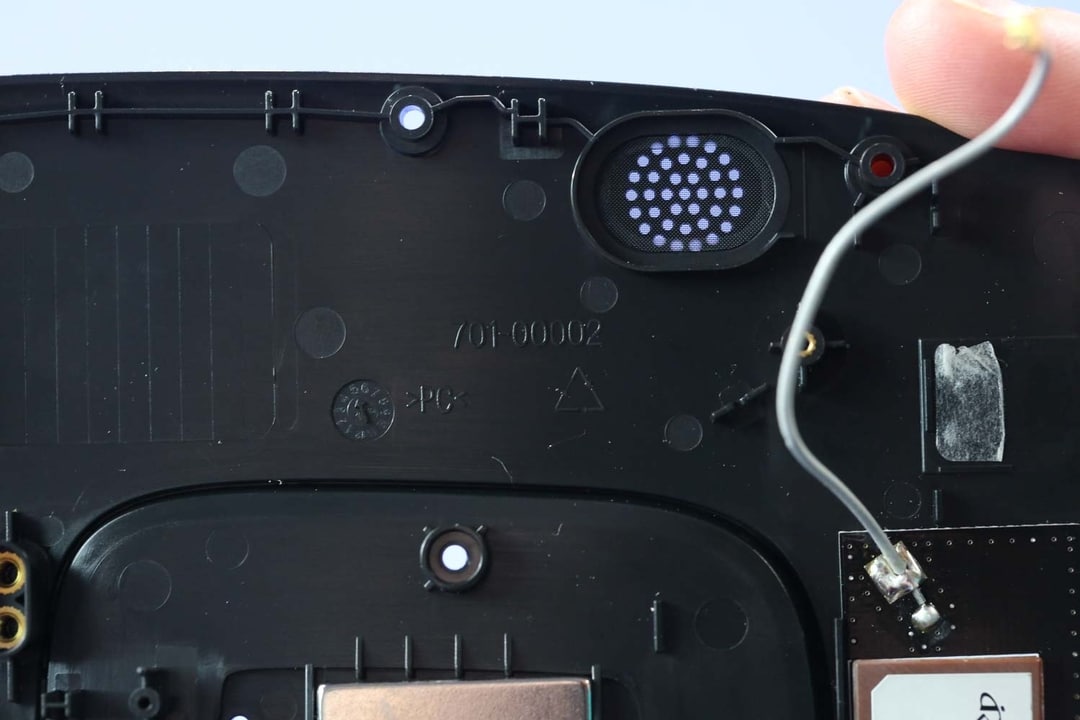

Mold markings on the top case indicate that these parts are made of polycarbonate (PC); the date of manufacture was May of 2016 (circular date indicators); and these parts are recyclable. 701-00002 is likely the Navdy part number.

This clever breakdown of complex parts could have been the result of careful forethought on the part of the Navdy team. It also could have been the result of a lot of back-and-forth with a manufacturing partner. One thing is for certain, though: This kind of design doesn’t happen overnight. Subdividing parts, creating molds, and then tuning the whole family of parts to fit together must have taken quite a bit of time and money.

Heat Sinking

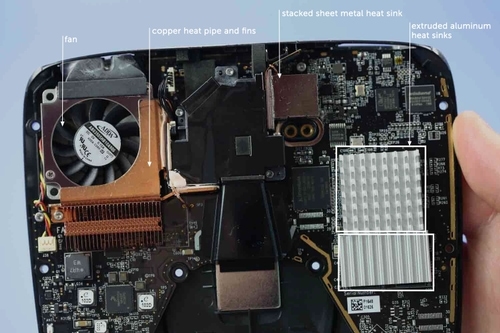

Projectors generate a lot of heat. Vehicle dashboards are one of the hottest environments that most consumer products ever encounter. The fact that Navdy put a projector on a dashboard means they did a pretty remarkable job removing heat from the device. Tearing down this product was basically a tour of different heat sink technologies. There are 5 different heat sinks on the Navdy, all optimized for different things.

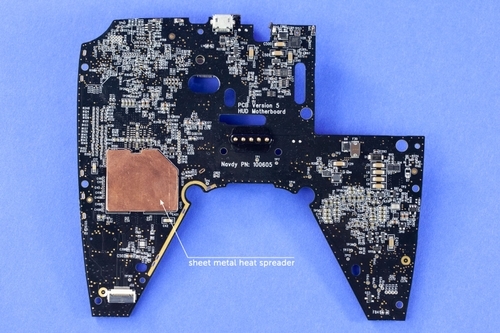

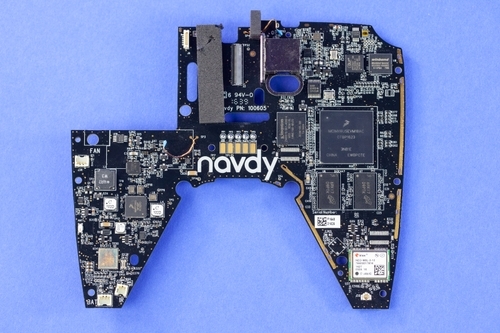

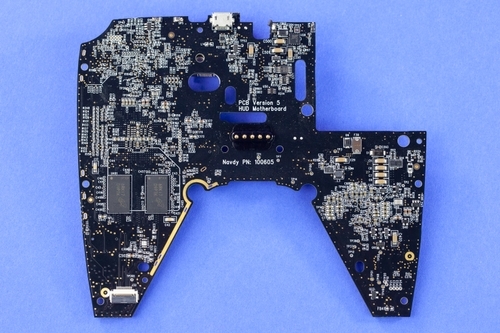

Two types of extruded aluminum heat sinks and a sheet metal heat spreader provide low-cost, effective cooling for the processor and memory ICs. The different types were likely selected to fit under the sloped ceiling of the enclosure. A stacked sheet metal heat sink was used to cool the DLP chip, making use of the fan to pull air between the aluminum plates.

A copper heat pipe and fins were used where the projector light source needed the most cooling. Copper is more expensive but was used for its high thermal conductivity. Placing this heat sink next to the fan takes maximum advantage of airflow. The PCB even has a few holes that appear to be to improve airflow.

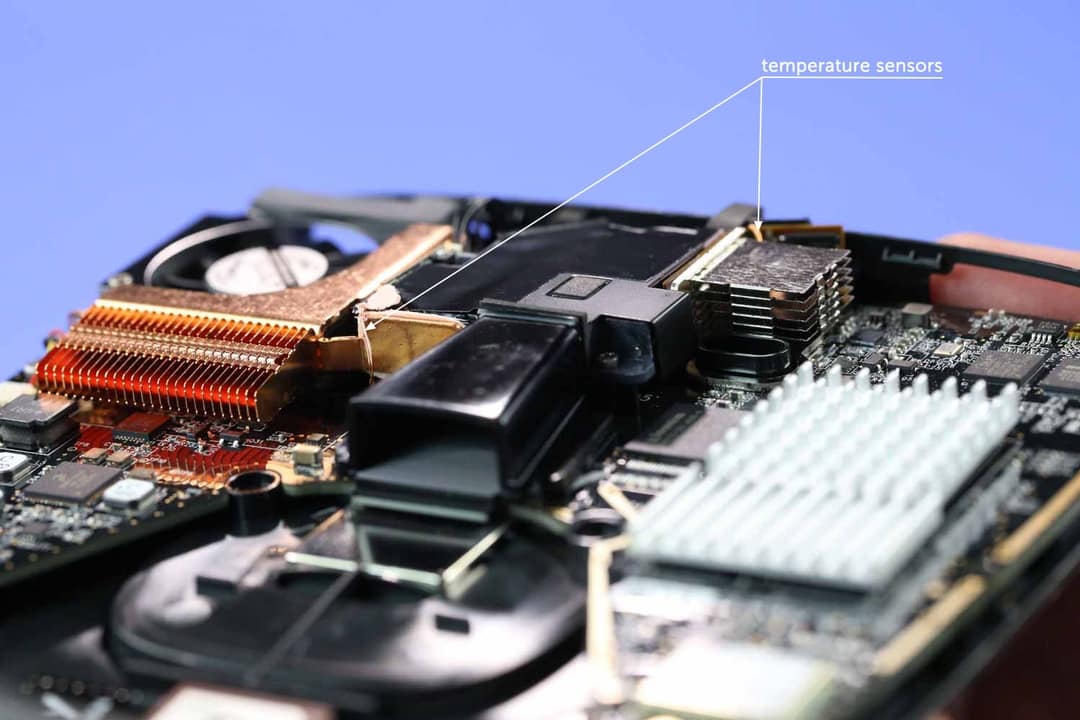

The Navdy assembly team added several pieces of foam and kapton tape to ensure all airflow went through the heat sinks around the projector. To close the loop, a couple of temperature sensors on flywires monitor the temperature in the projector heat sinks.

Clearly, the team put in a lot of thought and design here. The memory and processor ICs can get by with some cheap but effective aluminum heat sinks. But the huge thermal load from the projector requires a couple of custom heat sinks, with temperature sensors and a fan to provide active cooling.

This looks like something that probably required a significant investment of time and money to get right, before releasing the product.

Attention to Detail

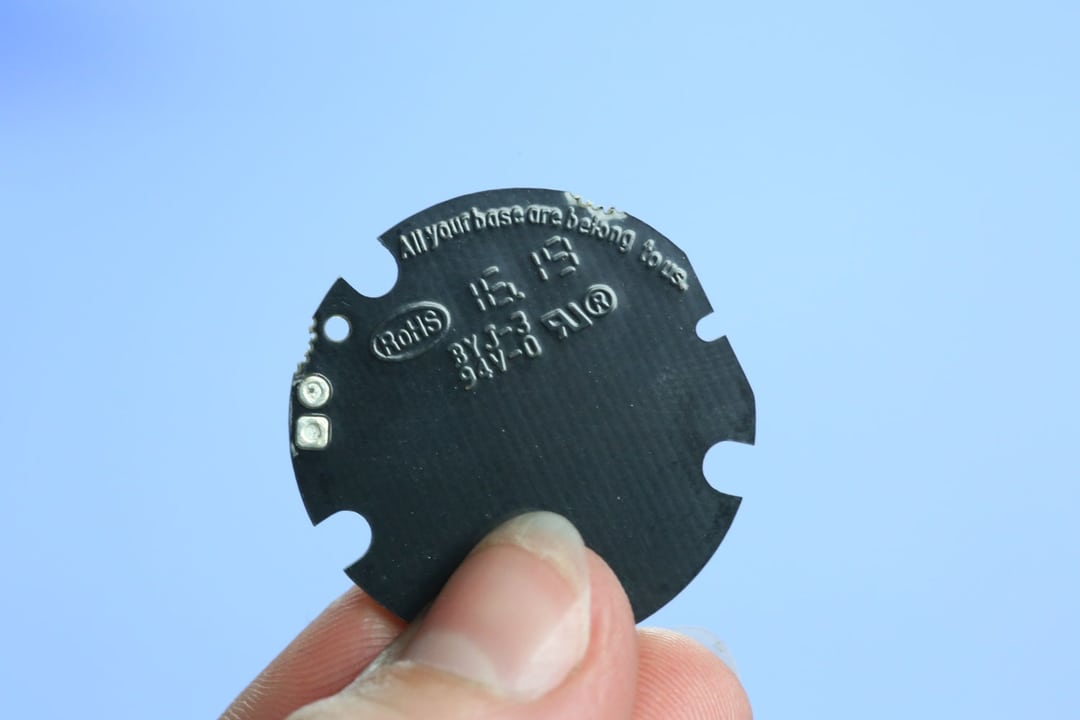

It’s clear that the Navdy team put a lot of thought and heart into creating every part of this system. Our favorite find? On the back of the battery PCB, inside the thumbwheel, the silkscreen reads, “ALL YOUR BASE ARE BELONG TO US.” (That’s a catchphrase from the 1989 game Zero Wing.)

The thumbwheel has a clever silicone band system that gently but securely attaches to steering wheels of different diameters and also prevents the user from installing the thumbwheel, unless the battery door is closed.

The FCC information for the thumbwheel is printed on the inside of the silicone band, which we thought was a neat solution. Ironically, this attention to detail might provide us some clues as to why Navdy went under.

As a new company, bringing a new product to market, Navdy was already taking on a lot of risks. Adding a relentless focus on details like these on top would have increased cost and development time and may have contributed to Navdy’s eventual demise.

Main Takeaways

From an engineering and design perspective, the Navdy HUD is a great product. It’s innovative, well-designed, and looks, as one reviewer put it, “Like your phone and a fighter jet had a baby.”

The injection molding design on this product is excellent. The team at Navdy did a great job with a challenging set of exterior surfaces by breaking large, complex parts into smaller, simpler parts. While this strategy can certainly be taken too far, the Navdy strikes a good balance between assembly cost and tooling cost. To top it all off, they did a great job hiding the resulting parting lines at corners, so the final product looked seamless. This is definitely a product we’ll look back to for injection molding inspiration.

We can also learn a lot about heat sinking from the Navdy HUD. Putting a running projector on a vehicle dashboard is a recipe for heat-related issues, but this product pulls it off nicely. With a fan for active cooling, temperature sensors to close the control loop, and a variety of different heat sinks, the Navdy is a great example of the application of different heat sink technologies.

Despite all of that, the company went under just a year after launching their first product. What happened?

One answer might lie in the meticulous attention to detail. Navdy spent a lot of time and money developing this product and may have bitten off more risk than they could handle on their first launch. Bringing a new product to market in a new category is already very challenging. Adding on a difficult heat management problem; a sleek, minimal set of exterior surfaces; and an uncompromising focus on detail would have further increased time and cost and might have just been too much to handle all at once.

There’s evidence that the Navdy team encountered more difficulties than they anticipated. Between the prototype they showed in 2014 and the units customers received in 2016, they cut features, like a microphone and aux output, and changed the exterior surfaces. The price rose from a projected $500 to $799 at launch but was dropped to $599, then $499, and eventually $399, perhaps indicating slow sales.

Did the team’s willingness to take on risk and attention to detail price them out of their market? It’s hard to say. Other factors, like supply chain, manufacturer agreements, and business strategy all play a part in setting prices. But one thing to consider as we design our products is whether (and when) we have to sacrifice product quality for the good of the business. Sometimes, getting the device into users’ hands (and proving to investors that there is a market) is more important than delivering a perfect product. If Navdy delivered a larger, cheaper, or boxier product with simpler heat sinking, would they have gotten a chance to launch a second version? It’s impossible to know. But it’s always a good time for us to consider how our work impacts both the user and the business as a whole. Maybe have another cup of coffee before the next All Hands and see what you discover.