Time to read: 11 min

While the presence of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields has been historically low, there’s a noticeable trend of growth in the number of women pursuing careers in engineering. This shift not only opens up new opportunities for women but also enriches the engineering domain with diverse perspectives and skills.

To illuminate these developments, our article provides an insightful compilation of five key findings and thirty notable statistics, showcasing the evolving participation of women in engineering and signaling trends for the future.

Key Statistics About Women in Engineering

These findings explore the following:

- How the number of women in engineering has made slow but steady gains in the US over the past few decades.

- The number of women employed in engineering roles in the US today.

- How much money women engineers earn globally compared to men in the same field.

- The age of American female engineers versus the age of their male counterparts.

- How the relative representation of women in engineering has changed in the US and Canada over the past five years.

The following is an in-depth examination of each of these five key findings.

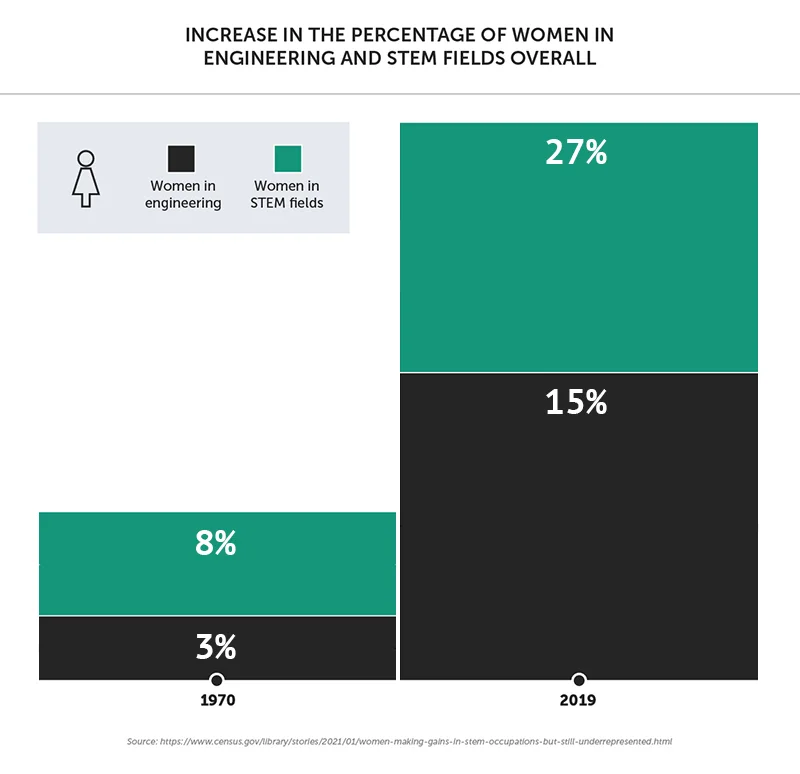

1. Participation of women in engineering gained just 12 percentage points in the US from 1970 to 2019 (Source)

According to the most recent information from the US Census Bureau, there has been a slow and steady increase in the number of women in engineering over the past few decades. In 1970, women comprised 38% of the US workforce. However, they represented just 3% of people employed in engineering fields. By 2019, women represented 48% of the U.S. labor force and the percentage of women in engineering increased to 15%.

This is part of a broader increase in participation of women in STEM fields in the US, with the percentage of women more than tripling over the course of five decades, from 8% in 1970 to 27% in 2019.

For context, the data also describes a historic trend of women choosing the social sciences. Women have overtaken men with a larger share of employed social scientists, from just 19% in 1970 to 64% in 2019. Women are relatively well-represented in the fields of mathematics at 47%, and life sciences and physical sciences at 45%.

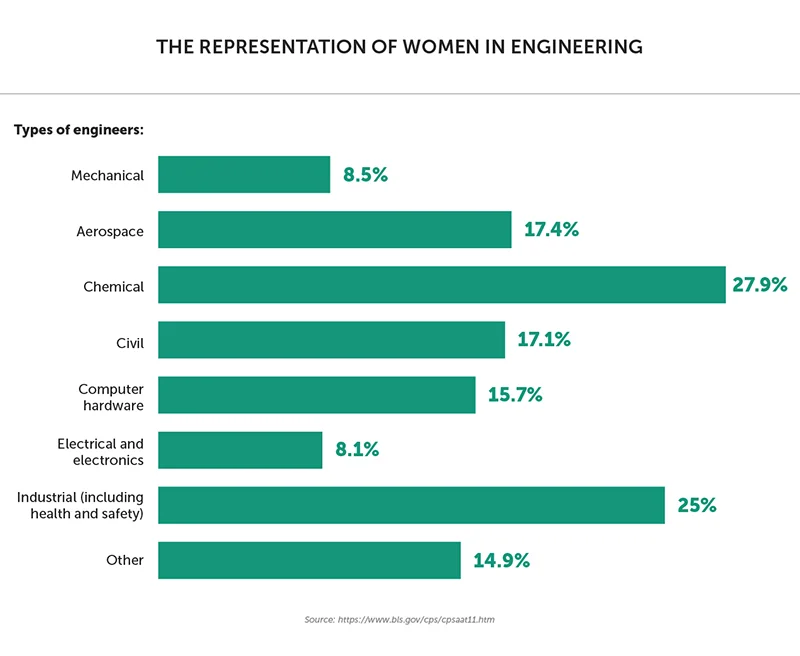

2. Women represented 16.1% of all employed persons in architecture and engineering occupations in the US in 2022 (Source)

With the total number of women in the “architecture and engineering” category at just over 3.6 million, the report from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics further breaks down the numbers. It reveals in greater detail how women are underrepresented comprising::

- 8.5% of mechanical engineers

- 17.4% of aerospace engineers

- 27.9% of chemical engineers

- 17.1% of civil engineers

- 15.7% of computer hardware engineers

- 8.1% of electrical and electronics engineers

- 25% of industrial engineers, including health and safety

- 14.9% of all other engineers

These numbers represent a significant gender gap between women and men in engineering professions, particularly in the fields of mechanical engineering and electrical and electronics engineering, where they comprise less than 10% of the workforce.

According to Zippia, women make up just 12.7% of nuclear engineers while men comprise 87.3%.

However, the gender gap is much narrower in biomedical engineering, according to research by CareerExplorer, which found that women represent 46% of that field, versus men at 54%.

In contrast, when considering the interest in pursuing a career in biomedical engineering, there is a noticeable gender difference. Only 36% of women express interest in this field, as opposed to 64% of men. This disparity in interest suggests that, while the current workforce is fairly balanced, future trends in the field might shift if these interest levels persist.

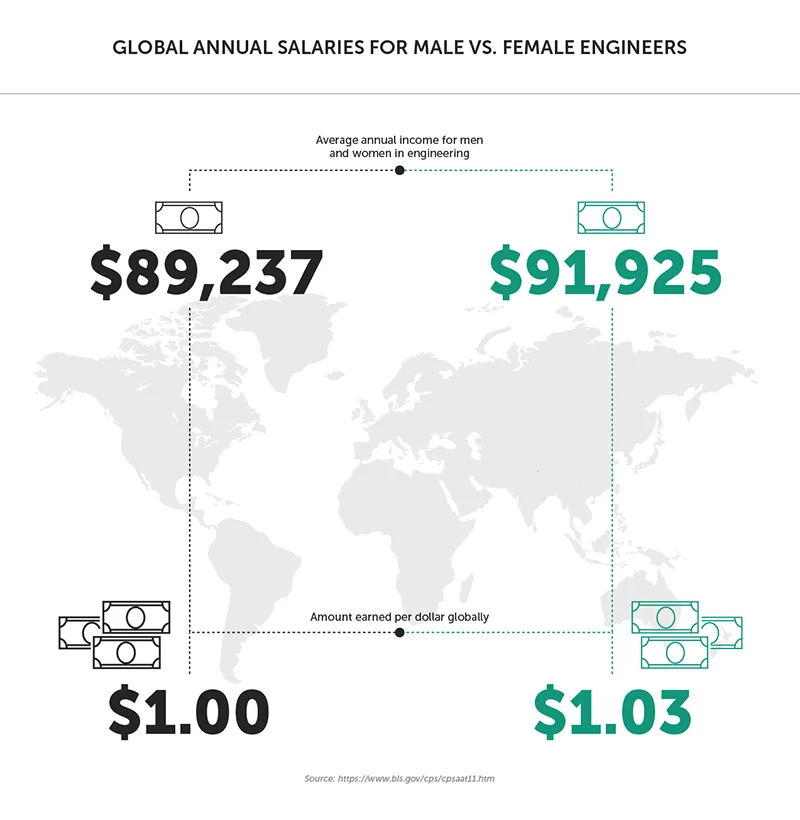

3. Globally, women in engineering earn 3% more than men (Source)

This 2023 report by Zippia found that women engineers made $91,925 annually on average, whereas male engineers earned an average of $89,237. This means that while men outnumber women in the global engineering workforce 86.3% to 13.7%, women earned more when in the same engineering fields.

Nuclear engineering is the exception where women earn just $.96 for every dollar earned by their male counterparts.

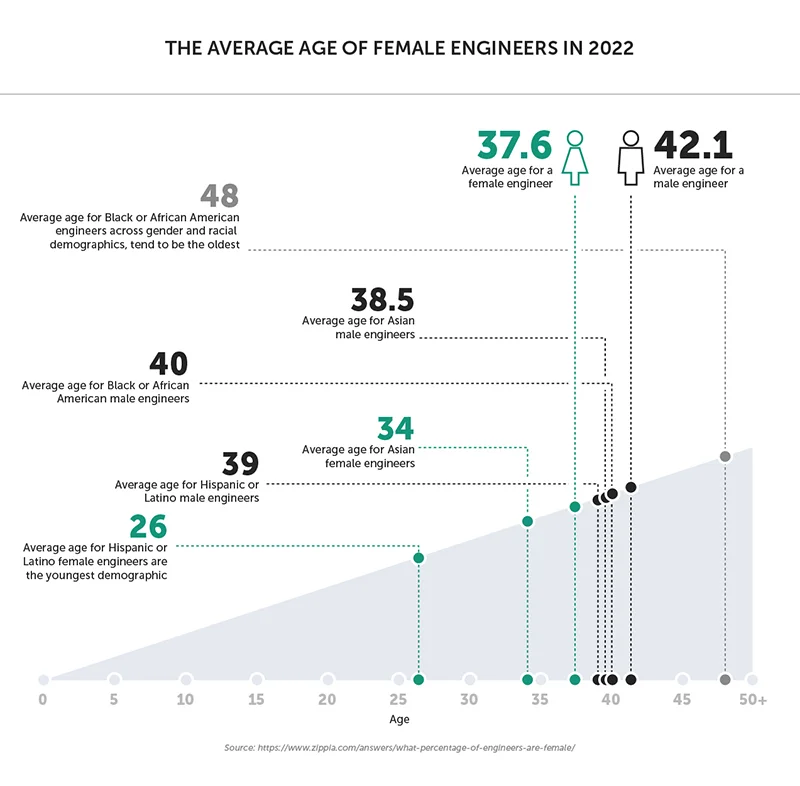

4. In the US, female engineers tend to be younger than men in similar positions, but Black or African American female engineers are generally older. (Source)

In analyzing the demographics of the US engineering workforce, we observe distinct age patterns that provide insights into career entry trends. Age serves as an indirect indicator to estimate the time when individuals start their careers in the field. This is because age, in a professional context, often correlates with the number of years one has been working in that field. Younger ages suggest recent entry into the profession, while older ages can indicate a longer presence.

- Gender Disparity in Age: Female engineers, with an average age of 37.6 years, are generally younger than male engineers, who average 42.1 years. This age gap suggests that a significant number of women may have entered the engineering field more recently compared to men.

- Variations Across Racial Groups: For Black or African American female engineers, the average age is 48, which is older compared to their male counterparts at 40 years. This might indicate different career entry points or career longevity within this demographic.

- Hispanic or Latina Engineers: The average age of 26 for Hispanic or Latina women engineers, compared to 39 for male engineers in the same demographic, indicates a recent surge in young women from these communities entering the engineering field.

- Asian Engineers: The smaller age gap between Asian female engineers (average age 34) and their male counterparts (average age 38.5) suggests a more consistent age of entry into the field across genders.

- White Engineers: White female engineers have an average age of 37, while White male engineers are older, averaging 42 years. This is the second-largest age disparity, highlighting different career entry times.

The age data acts as an indirect indicator, shedding light on the times when various groups likely start their engineering careers. Understanding these trends can give insights into the evolving dynamics of gender and racial diversity in engineering, as well as predict potential future shifts in the profession.

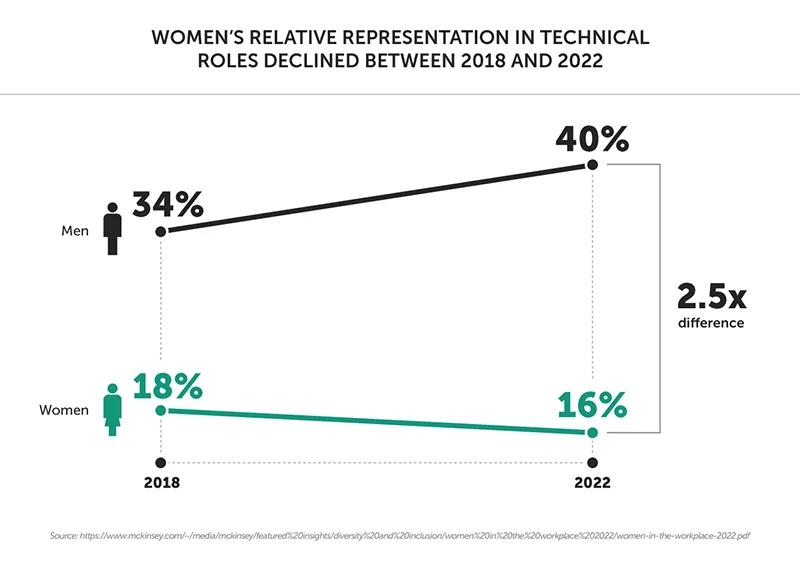

5. 32% of women in engineering and technical roles are ‘onlies,’ meaning they are often the ‘only woman in the room’ – and they are underrepresented in leadership roles (Source)

The relative representation of women in engineering and technical roles in the US and Canada has declined in the past five years. In 2018, 18% of women self-reported working in an engineering or technical department, versus 35% of men. However, in 2022 the percentage of women decreased to 16% and the percentage of men increased to 40%. This represents a 2.5x difference between men and women.

According to McKinsey, female engineers being “onlies” may contribute to women in the field facing disproportionate bias compared to men. For example, their judgment is more likely to be questioned and they are more likely to be overlooked for advancement opportunities.

For example, in the engineering and industrial manufacturing talent pipeline, fewer women than men are represented in leadership roles. Only 23% of C-suite executives in engineering and industrial manufacturing are women, compared to women representing 33% of entry-level positions in those industries.

Meanwhile, the proportion of women in other leadership roles is also lower than men, with women representing 25% of managers, 25% of senior managers, 23% of vice presidents, and 21% of senior vice presidents.

With engineering and technical roles among the fastest-growing and highest-paid in the US, disadvantages due to gender-based discrimination may discourage participation among women and exacerbate inequality in representation and earnings. It may also lead to fewer female role models and women in mentoring roles in those industries.

Additional Women in Engineering Statistics

These statistics about women in engineering not only reinforce our five key findings but also provide insights into additional aspects of the engineering landscape in relation to women. They draw attention to trends in STEM education, both in the US and globally, and how these trends influence career choices and the representation of women in engineering fields.

Additionally, these statistics indicate how organizations can leverage this promising segment of the STEM workforce for a competitive edge.

Numbers by Gender

1. In 2023, men outnumbered women in the global engineering workforce 86.3% to 13.7%. While this percentage of women in engineering is a decrease from 14.88% in 2020, figures over the years indicate a general increase in the percentage of women employed in engineering worldwide.

2. 35% of women engineers in America are in the field of environmental engineering, while only 9% chose mechanical engineering and 8% are in petroleum engineering (Source)

3. There were just 8,060 women materials engineers versus 43,172 men in the same industry in 2022. (Source)

4. 68% of women in STEM in the US had science and engineering (S&E) jobs in 2021. This included technologists, technicians, and instructors. (Source)

5. In 2021, 65% of people employed in the S&E field in the US were women. (Source)

6. There were 6.6 million women engineers and scientists in the EU in 2020, accounting for 41% of the workforce in similar fields. (Source)

7. The percentage of women in engineering roles in the UK increased from 10.5% to 16.5% between 2010 and 2021. (Source)

8. The percentage of women working as science and engineering associate professionals in the UK increased from 18.8% to 28.1% from 2010 to 2021. (Source)

9. The percentage of women employed as corporate managers or directors in the UK increased from 11.2% to 15% from 2010 to 2021. (Source)

Inequality and Discrimination

10. 45% of female engineers in Australia report not having equal opportunities as their male counterparts, and nearly one out of five report that women are being excluded or bullied at work. These are the main contributors to women leaving engineering fields. (Source)

11. Women in the US are credited less often in science and engineering academia than men. If we define “credit” as being named an author, women comprise just 34.85% of the authors on a team, even though they represent 48.25% of the workforce. (Source)

12. In higher education, female graduate students are more often excluded from academic authorship than men, with 42.95% of women reporting exclusion versus just 37.8% of men. (Source)

13. Among graduate students, only 14.9% of women were found to be named authors on academic papers, versus 21.3% of men in the same field. (Source)

14. Female graduate students are more likely to be research staff (47.8% vs. 28.7% male) rather than faculty (11.3% vs. 19.7% male), including STEM fields. This contributes to women authors being 4.8% less likely than men to receive credit. Faculty members have the highest “ever authorship” for academic papers at 45.7% while the rate for research staff is only 8.6%. (Source)

15. In Australia, a higher percentage of female engineering students (12%) compared to male students (5%) felt excluded by their peers and/or educators while in college. (Source)

16. While women represent 33% of scientific researchers in STEM fields, they only make up 12% of national science academy members. (Source)

Engineering Education in America

17 . In the US, 21% of women choose an engineering major in college (Source)

18. 44.2% of American women in STEM had a bachelor’s degree in 2019 compared to 41.9% in 2010 (Source)

19. The percentage of women working in STEM occupations without a bachelor’s degree has remained almost the same over a decade, with a decrease from 26.1% in 2010 to 25.8% in 2019. (Source)

20. More 32% of female STEM majors in the US switch to another major outside of STEM before they graduate. (Source)

Engineering Education in the UK and EU

21. Only 18% of the UK’s total first-year undergraduates in engineering and tech are women, even though women represent 57% of all first-year undergraduates. (Source)

22. Of female first-year undergraduates in the UK who have studied A-level math and/or physics, only 22% studied both math and physics, 31% studied physics only, and 50% studied math only. (Source)

23. In the UK, more women than men in technology and engineering degree programs earn first-class honors, at 48.6% of women versus 41.9% of men. For context, 35.1% of women studying all subjects qualified with the same honors, showing a steep increase in enrollment among women studying engineering and tech. Similar progress rates of female versus male students can be observed in the workplace 15 months after they graduate. (Source)

24. Only 42% of girls aged 7 to 19 in the UK consider engineering to be a suitable career for them, versus 61% of boys. Moreover, only 35% of girls said being an engineer would fit who they are, versus 53% of boys. (Source)

25. Preconceptions about gender differences in scientific and mathematical ability are further shown by the fact that only 24% of UK girls aged 7-19 said they could “yes, definitely” become an engineer, versus 33% of boys. Further, 41% of girls said “yes, probably” versus 49% of boys. (Source)

26. In the European Union, only about one-third of STEM graduates are women, with twice as many of their male classmates graduating with similar degrees. (Source)

27. There were 7.2 million women engineers and scientists employed in the EU in 2022, while their male counterparts numbered over 10.5 million. (Source)

Engineering Education in Australia

28. In Australia, 91% of women in engineering said they excelled in STEM subjects in high school. For context, only 59% of women in benchmark fields said the same. (Source)

29. Fewer Australian women consider careers in engineering prior to high school than careers in science, at 21% versus 35%. (Source)

30. In Australia, only 16% of engineering graduates are female and represent only 13% of employed engineers. However, Australian women in other STEM fields have more balanced representation. (Source)

31. Roughly three out of four Australian women never considered studying engineering, while just 7% seriously considered it and 16% considered it briefly. (Source)

32. Of Australian women who considered engineering but decided against it, even though they self-reported that they excelled in math and/or science, the most common reason was fearing they weren’t good enough at science, at 29%. The next most popular reason was fearing they weren’t good enough at math, at 25%. (Source)

Important takeaways from these women in engineering statistics

Here are some major takeaways from the insights these women in engineering statistics offer into the current and future engineering career prospects for women:

- Progress for women in engineering is slow not only in the US but also internationally. However, women continue to enter STEM degree programs and join the workforce in related industries, so the percentage of women in engineering will likely continue to increase.

- Contributing factors to the gender disparity in engineering fields include discrimination, lingering cultural reservations in the academic and professional spaces, and preconceptions about the educational aptitude of men versus women.

- While the gender gap in engineering is still significant at the educational level as well as the career level, the gender pay gap has been closed and, in some fields, even reversed.

- The slow but definite gains for women in employment in engineering fields is contrasted by a more rapid increase in women offering professional engineering services as independent providers.

Women who are taking up entrepreneurial roles by offering professional engineering services may find career potential in small-scale custom manufacturing like 3D printing, casting, and tooling. Female-led engineering companies could streamline manufacturing and other related processes from concept to delivery, improving the industry overall while helping bridge the gender gap within the engineering fields.

On the academic front, this may encourage more young women to get into one of the several established engineering fields, and even some that have recently grown in prominence, such as AI engineering.

Fictiv — Helping solve your custom engineering challenges

Fictiv is the operating system for custom manufacturing that makes it faster, easier, and more efficient to source and supply mechanical parts. Its intelligent platform, supported by best-in-class operations talent, orchestrates a network of highly vetted and managed partners around the globe for fast, high-quality manufacturing, from quote to delivery. To date, Fictiv has manufactured more than 28 million parts for early-stage companies and large enterprises alike, helping them innovate with agility and get products to market faster.

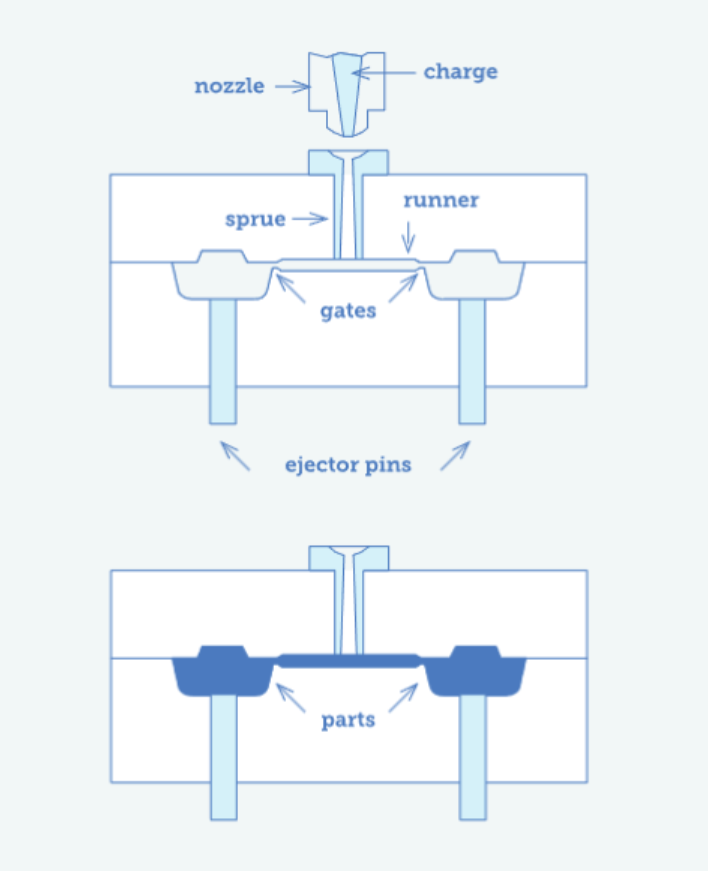

Fictiv’s portfolio of optimized manufacturing services includes 3D printing, CNC machining, urethane casting, and injection molding.