Time to read: 6 min

If you work professionally in product development, or even if you tinker in your free time, you already know that a single misstep can be the difference between releasing your product on time or being late to market. Sometimes, that’s the difference between success and failure in hardware design. It’s for this very reason that we all strive to make as few mistakes as possible (zero is ideal) and NEVER repeat the same mistake twice.

Of course, mistakes come in in all sizes, and the resulting design changes have varied impacts on your project. What you might not have considered is that the timing of those design changes plays a huge role in their impact on a project. This article will discuss the high costs associated with making late-stage design changes during a product design lifecycle.

The Benefits of Failing

The words “fail” and “failure” typically have quite the negative connotation. In fact, I’ve often heard those two words referred to as “F-Words,” not to be repeated out loud. However, in product design and development, failing is part of the game. You not only expect to fail, you plan for it.

If you’re trying to design the lightest tennis racquet on the market, for example, you will likely design a racquet that is so thin that it will crack or completely break during its first use on the court. Although the first iteration of the racquet “failed,” it was necessary to know that the particular thickness you started with was too thin. The next iteration will be slightly thicker.

Of course, this process will be repeated, until you can determine the absolute thinnest racquet that will still hold up to regular usage for a given material. If you had designed a thicker racquet from the start, the racquet might never have broken during usage. While many people would argue that this is a great thing (the product never “failed”), it certainly would not result in the absolute lightest racquet on the market.

Since creating the lightest racquet on the market is your actual goal, the inability to meet that goal would be the true failure. The point here is that failures (design changes) are a necessary part of product design and development.

The Benefits of Failing Sooner, Rather than Later

Now that we’ve established that failures (design changes) are crucial, let’s talk about when those failures occur during the product development lifecycle.

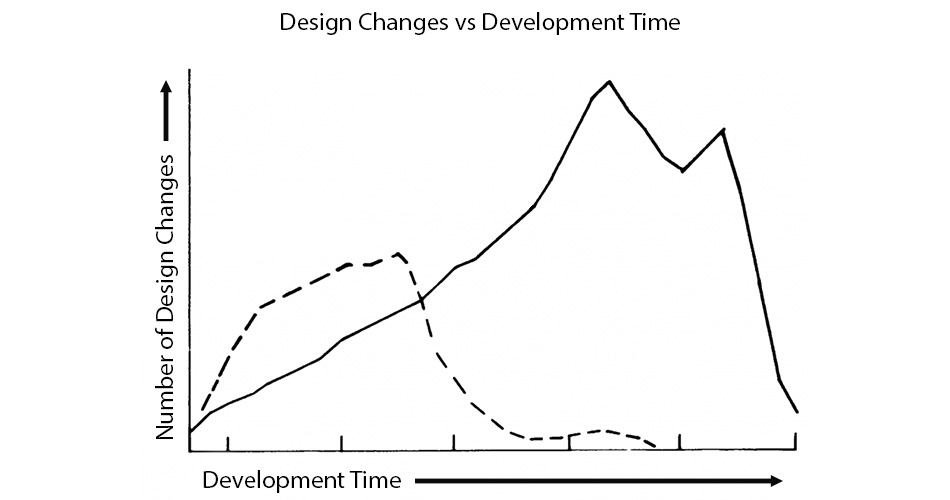

The graph above shows two different product development lifecycles, tracking each’s development time vs. the number of design changes. One of those development cycles is much longer than the other. Why? Because that development cycle had many more design changes LATER in the development cycle.

As it turns out, the effect of a given design change to the project’s timeline increases with time.

The earlier you iterate your product’s design, the better off you are. Don’t forget that time is money. Being late to the game is costly in and of itself.

Want to learn more about the development strategies shown in the graph above? You can learn more about them in my article “Breaking Down the Walls of Product Design w/ Concurrent Engineering”, in which I discuss the differences between “concurrent engineering” and “sequential engineering.” You’ll have to read the article to find out which approach is the industry standard.

Example of a Costly Late-Stage Design Change

You’re one month away from approving your product for production, when someone realizes that the product is missing a necessary “permanent” warning sticker in both English and French, as per some certification requirement to which your company self-certifies. Without the sticker, the product can’t ship to Canada or several other countries. The language of the warning (in English) has not been decided (there is some room for interpretation in the standard) and therefore is not ready for translation into French.

Someone, likely the industrial designer and/or the graphic designer, has to decide where to put the sticker on the product, in such a way that it complies with the certification standard, but he/she can’t do so until he/she knows how much room it will take. Worse yet, none of your factory’s standard stickers are considered permanent enough. So you’re also considering an alternative, which would be modifying your product’s injection mold so that the “sticker” will be permanently molded into the product instead.

All in all, a lot of work has to be done in order to meet the certification requirement so close to production.

Sound somewhat familiar?

It just goes to show that a single oversight discovered late in the game can have a cascading effect that will clearly cause a serious delay ($$$) and add costs ($$$) to the project. However, if this issue were discovered early on, it wouldn’t even be considered an issue. It would simply be another task in the list.

Other activities that increase cost for late-stage changes include tooling and assembly-line changes during production or the possibility of recalling cars for retrofit.

When Design Changes are the Costliest

The production stage is the costliest time to make a design change. If you are in a situation where you have to modify a product that’s already in production, hope you hear the words “running change”. In the case of a running change, you don’t worry about product that has already hit the shelves. Instead, you concentrate your efforts on fixing the product for future production only.

In most cases, the consumer never even knows about running changes. Would you ever notice, for example, whether a product’s screws were changed from zinc plated steel to stainless steel? Probably not.

Would you notice if the wall thickness of an injection molded product were changed from 1.3mm to 1.5mm to improve the product’s stiffness or reduce the likelihood of breakage? Again, probably not.

There’s another category of production changes, however, that you certainly have heard about. If fail and failure are considered “F-Words”, I have another one to add to the list: the “R-Word”, which stands for recall. For those of you that don’t already know, a recall is a situation that occurs when a serious problem is found in a product that is already on the market.

In addition to fixing the product for future production, the company at fault typically either buys back all of the defective products or pays for those products to be reworked. If you haven’t done a gut check on the math on this in your head yet, you should know that this is by far the absolute most costly product design change.

Can’t think of any examples of this happening? Well, your car has probably already had a part recalled, and if it hasn’t, you might want to check with your local dealership, as there is likely a recall out there that you didn’t know about.

Either way, you will certainly have heard of the recent Volkswagen TDI emissions recall, which is expected to cost Volkswagen over 15 billion dollars. How about the Boeing 787 Dreamliner battery incident of 2013, where an entire fleet of brand new commercial jets had to be grounded while a battery problem was assessed and eventually fixed? That recall cost Boeing 600 million dollars.

Summing Things Up

As mentioned before, you can and should expect to run into issues that cause design changes. It’s part of the product development lifecycle, and you not only can’t avoid it, you shouldn’t. Design is iterative and should be treated as such. However, you should expect that any design changes near the end of your product’s timeline will have a much bigger cost than an earlier design change. Design changes after production is underway are the absolute costliest.

It’s for that reason that companies around the world have adopted a “fail quickly” policy. They want you to try out ideas right away and iterate them as quickly as possible, until the best solution is found. This strategy results in the best product in the shortest amount of time and for the lowest cost.

So, spread the word. Tell your friends to get out there and start failing, but make sure they do it right away because the longer they wait, the higher the cost…