Time to read: 7 min

All startups have challenges. Funding. Staffing. Marketing. Sales. Customer service. If they’re hardware startups, they need to add supply chain, prototyping, and manufacturing to the mix.

That’s all assuming their product or service is rated G.

Lioness, a startup in the hardware manufacturing space, has an extra challenge—they design and manufacture vibrators for women. This is a space that has been taboo for a long time. Not only has it been difficult for people to talk about this particular type of product, there have been few best practices and lots of poorly designed models.

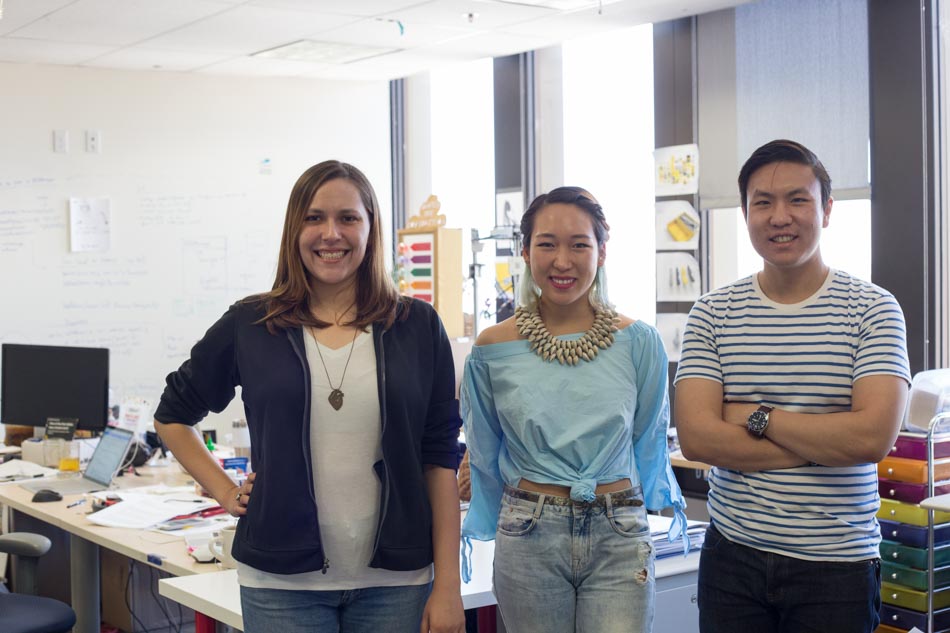

In this Spotlight, we sit down with the three co-founders of Lioness to talk shop about innovating an intimacy device—with straight faces.

Disrupting a sensitive space

Does the vibrator space really need disrupting?

Founder Liz Klinger thinks so, though she doesn’t think of Lioness as just disrupting the vibrator market.

“What we’re doing, ultimately, is changing the way we think about our sexual health. The vibrator is just a means to that end…albeit a very direct one,” she says.

With a background in human sexuality, design and marketing, and experience selling intimacy products to women all over the country, she knows what she’s talking about.

“The women I sold [these products] to were of very different backgrounds and ages,” says Klinger. “They all had questions about their bodies and sex lives that they felt they couldn’t talk about with anyone else. There were women in different stages of life—for example, pre- and post-pregnancy, or post-menopause, all of which impact the way a woman’s body responds, not just in sex, but in general. They had all of these questions and concerns they could not explore on their own because the information wasn’t out there and because it can be a difficult subject to talk about.”

Another issue is that the vast majority of intimate devices for women has traditionally been designed by men—largely, explains Klinger, because of the lack of women in the field of engineering.

Anna Lee, engineering lead, agrees.

“Women’s health products in general are really neglected—but especially when it comes to sexual health,” Lee says. “Our product is by women, for women.”

James Wang, software and business lead for Lioness chimes in.

“What we’re doing is pushing the boundaries of a product that’s been largely ignored, and change the way these types of devices are perceived,” he says.

Ironically, it’s precisely because vibrators and other intimacy products are a bit taboo in our society that the waters are not roiling with predators.

“The one thing we have not worried about is competition,” says Wang. “There’s a lot of taboo and stigma around [vibrators]; that’s part of what has isolated this market, and it makes the pipeline [for finding talent] a lot smaller.”

How smart can a vibrator really be?

Very smart, it turns out.

“Lioness has different sensors that can measure vaginal contraction, temperature, and positioning,” says Wang. “It measures a woman’s patterns and rhythms and helps women assess how long it takes them to become aroused or to have an orgasm.”

Lee explains that the data is stored in the vibrator until the user syncs it with her phone, where she can view it in the form of graphs and customized, individually tailored insights. The device also connects with an anonymous online community where people can ask questions.

Wang says that all of this data is not necessarily intended to change behavior.

“It can help spark a conversation about your body,” he says. “That’s the high-level value proposition of Lioness—the information and insight it can give you.”

This takes data security to a whole new level

A vibrator is one of the most intimate products you can buy, so the idea of a “smart” vibrator might send unpleasant frequencies to some users. The Lioness team takes data privacy seriously, however.

“The Internet of Things is actually easily hackable,” explains Wang, mentioning Bluetooth as an example of a popular but rather insecure data communication channel. “We apply bank-level security on the server side of the app. Lots of redundancy; everything is encrypted and uses a secure channel. There is no open communication among any parts of the product. That’s the first level of security. The second level is that even if someone could download data, they would not be able to associate the data with individuals.”

The team is taking security so seriously, in fact, that they’re writing their own security stack from the ground up, to make Bluetooth communications secure. Only then will they consider using it.

So…how do you beta test a vibrator?

Klinger laughs.

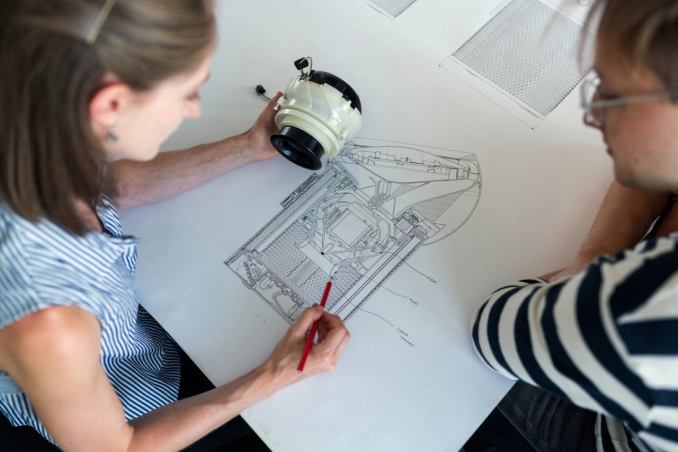

“It’s difficult to do prototyping and testing for a product like this. It’s not like Fitbit—you can’t just go around to random people in public and show it off,” she says. “We did ethnographic interviews as well as functional studies, with well over 100 people. We covered as many cultures and demographics as we could. We showed our clay models to different women and got their feedback on what it looks like, and then when they tried out the functional prototype, we asked some pretty blunt questions.”

But blunt questions apparently didn’t deter the ladies.

“We had to close our waitlist because so many people were willing to test it and provide feedback,” says Lee.

The only trouble, adds Klinger, is that you can’t re-use prototypes. “It’s one prototype per user,” she says.

We think about that for a split second and realize she’s right.

“We had to make [the prototypes] by hand, each one of them,” she explains. “Technically, we could have sterilized the parts, but there’s that psychological factor you simply cannot ignore.”

Prototyping for intimacy—and budget

Unlike other types of products, like, say, coffee grinders and photo displays, a vibrator is just about the most intimate object you can manufacture. So the one-to-one prototype-to-tester ratio can certainly drive beta testing costs through the roof. All in all, it took the Lioness team two years of prototyping and a lot of their own sweat equity before they came up with the final product.

“We bootstrapped with our own funding and resources,” says Klinger. “We got into the Foundry [an accelerator in Berkeley], which gave us space and 3D printers. We talked to Dave Evans [of Fictiv] a lot. We couldn’t have done it without the 3D printing ecosystem that exists now—that was critical for us to do it cheaply. Eventually, we got our own 3D printer just because we had to iterate so often, but we still accessed other 3D printers—we went through hundreds of prototypes that we never ended up showing to anyone.”

Klinger had done a lot of studio art and sculpture, as well as engineering, and was acquainted with the design thinking philosophy of “start simple and get user feedback early on in the process.”

“A lot of the [existing] vibrators had various things I thought could be done much better, everything from the motor (either too weak or too strong), to the shape and size, to the handle (the ergonomics were wrong),” she says.

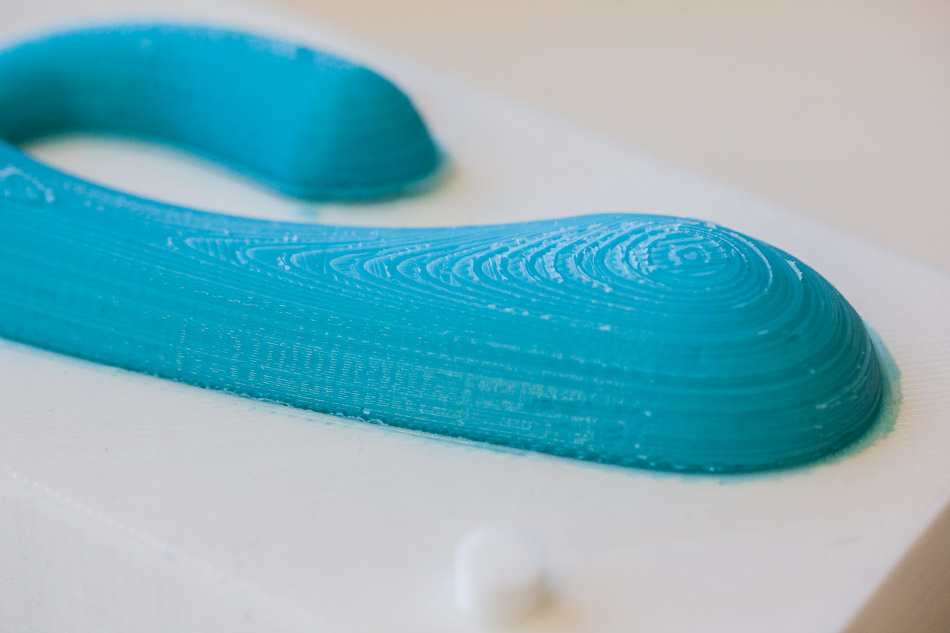

At the same time, she explains, the prototyping for a product like this is much finer than others because it comes into close contact with the body. “You cannot have imperfections or holes, the shape has to be right; there are so many considerations and intricacies you need to take into account.”

The team made 70 different prototypes: 50 for the form factor, and 20 for function. The latter were actually two distinct prototypes with ten variations each.

On the form factor side, the team would design and build a dummy vibrator, just for the shape and the silicone covering, and turn to their beta tester group to get feedback. Women’s bodies, of course, vary, and Lioness wanted to respect those variations and account for them in the product design. For example, the team worked on a lot of different designs to account for the variations in distance between the clitoris and the vaginal opening. The result was a flexible clitoral nut that adapts to each woman’s body.

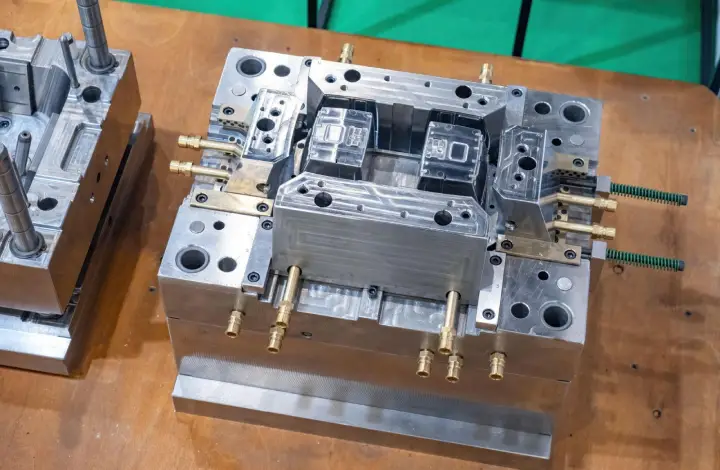

“There’s still going to be a limit to how adaptable it is,” says Wang. “That’s inevitable with hardware devices that are molded to the body, in general. But we think we’ve done a great job compared to the rest of the market.”

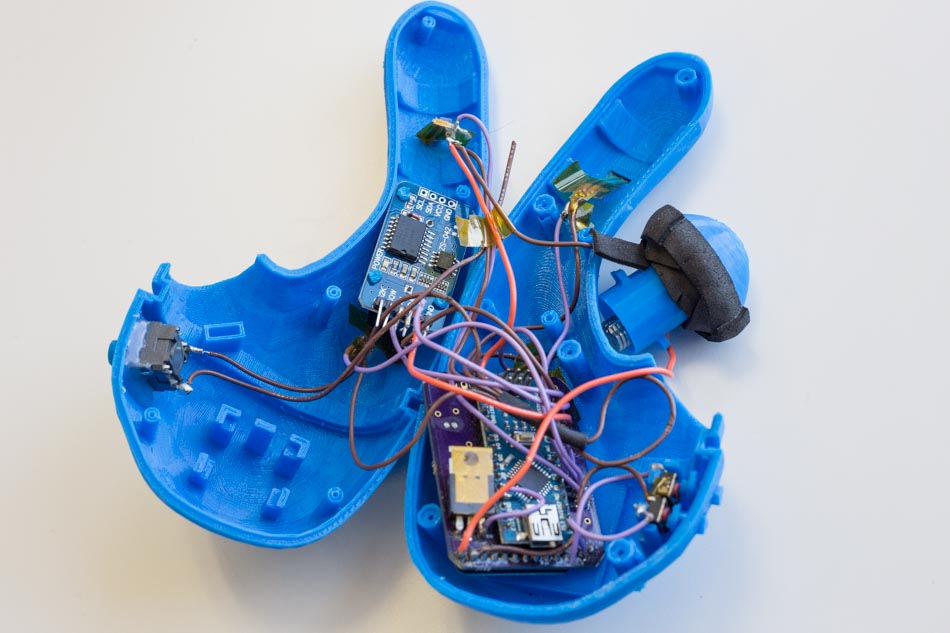

At the same time, they worked on the functional prototypes.

“We did five runs per [functional] prototype,” says Lee. “Each one took a day. So it took us five days to produce prototypes, send them out, and get feedback. Then we’d tweak stuff and do another run.”

Debugging could take three days—and sometimes the team would have to deal with mechanical failure, says Wang: “As in, something would fall off because the whole unit was vibrating.”

“If you open up one of our vibrators,” says Wang, “it looks like an early smartphone. It’s not just a battery and a motor like conventional vibrators have—it also has a full-blown microprocessor, battery management, and a sensor suite from force to temperature to accelerometer. We have all the pieces you’d expect in an IoT device in terms of intelligence and sophistication. On top of that, we’re also implementing firmware over the air.”

In other words, wireless software updates, so even after a customer buys it, she can continue to improve and upgrade her device.

The final frontier of IoT may be the most intimate

As the Internet of Things space matures, so might our sense of what’s taboo and what’s worth knocking down long-held barriers for. After all, neither silicone nor silicon makes any judgments about how we humans use our devices. They simply work. It’s our job to make sure that they do so in a manner that enhances and enriches lives, while maintaining the privacy and intimacy we inherently cherish.

In the meantime, let the Lioness roar.